About the Author: Lee Anna Maynard, PhD, is a freelance writer, editor and scholar currently based out of Augusta, GA, where she is on faculty with Augusta University. She received her PhD in English from the University of South Carolina and was an Assistant Professor in the Department of English and Philosophy for Auburn University Montgomery. She has served as the managing editor for a regional magazine and her first academic volume, which explores the role of boredom in the Victorian novel, was published in 2009.

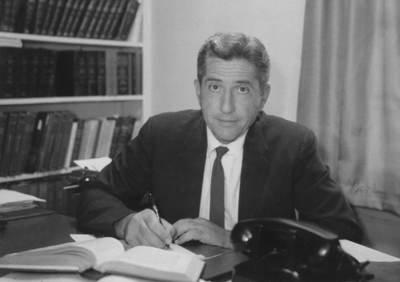

New Leader at the Helm: John Watkins

For almost ten years before becoming its executive director, John Watkins had been an integral part of the Alabama League of Municipalities. As League Counsel and Staff Attorney, he learned firsthand about the growing and changing needs of the towns and cities the League represented, and when he assumed the duties of Executive Director, the administrative and leadership experience he had earlier gained as Prattville’s City Manager and a municipal judge served him well.

Born in Faunsdale, Alabama, in 1919, Watkins experienced small-town life prior to embarking on an ambitious course, graduating from Sewanee Military Academy in Sewanee, Tennessee and studying at the University of the South and the University of Alabama before entering the Naval Air Force upon his college graduation in 1941. Following active duty during World War II, Watkins returned to the University of Alabama in 1945 and earned his law degree. After receiving his juris doctor, he practiced law in Prattville for five years before becoming a judge.

In 1965, Watkins swept into his new role as Executive Director of the League of Municipalities on a tide of good feeling from the League’s constituents, as he had been the lead architect of recently-passed legislation that would streamline and standardize what he called the “real hodgepodge” of laws bedeviling municipal elections. The changes Watkins helped implement have saved Alabama’s towns and cities thousands upon thousands of dollars in the almost fifty years since the Legislature passed the reform bills, as the costs of processing write-in ballots and running elections in uncontested races have been eliminated. Watkins’ quiet demeanor and soft-spoken gentility were in direct contrast to the brash style of his predecessor, but he, like Ed Reid, would steer the League successfully through times of progress, upheaval, and alteration.

The Turbulent 1960s

America suddenly seemed younger and less invested in conservative tradition in the 1960s, due in large part to the coming of age of an astonishing 70 million post-World-War-II-boom babies. These young adults attended college in record numbers, listened to forms of rock-and-roll and rhythm-and-blues music their parents and older generations found even less acceptable than Elvis and the (early) Beatles, and questioned the norms of society and politics. America’s sense of confidence and international dominance was shaken by the increasing power of the Soviet Union, especially as cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person in space at the outset of the decade, orbiting the earth once in the Vostok 1. More chillingly, the Soviet Union erected the Berlin Wall and detonated the largest nuclear device in history as part of an unannounced test. American involvement in the geographically remote but ideologically significant Vietnam War spawned serious debate and generational divides in the United States. Political assassinations and attacks on houses of worship and children (such as the Birmingham church bombing) took the reactionary violence against the civil rights movement and other forces of change beyond protestors and demonstrators to the heart of American communities as well as the foremost symbols of the country.

These mounting tensions of the age can be seen in critically-acclaimed artistic productions of the 1960s. Though family-friendly musicals like The Sound of Music and My Fair Lady were greeted with cheers at movie-houses around the country, darker and bleaker films like The Graduate, Midnight Cowboy, and Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb enthralled critics and Friday-night viewers alike. Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are and Madeline L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, award-winning children’s and juvenile fiction of the time, both depicted destabilized and slightly disturbing versions of childhood and youth where adults didn’t always have answers or good intentions and children were on their own to survive or find solutions. Close to home, Alabama author Harper Lee won the Pulitzer Prize for To Kill a Mockingbird, her powerful novel interrogating the possibility of moral, social, and legal justice in a rigidly segregated small, southern town.

The Changing Face of the League

Through the struggle for civil rights in Alabama was long and arduous, the late sixties and early seventies saw the state’s first elected municipal officials of color of the twentieth century, including Mayor Freddie Rogers of Rogersville, Mayor Andrew Hayden of Uniontown, and Councilman Richard Arrington of Birmingham. Women, too, began to be more electable in Alabama as the 1960s drew to a close, and these minorities of race and gender were soon serving as committee members in the Alabama League of Municipalities. Executive Director Watkins made certain all his league members understood the changing legal landscape and he positively employed his trademark calming presence, promoting quiet acceptance among those municipal leaders antagonistic to these new social and political realities.

The face of the League was changing in other ways, too. Dr. James Hardwick, Mayor of Talladega and outgoing President of the League, exhorted his fellow League members to “build the cathedral” at the 1965 convention. Mayor Guthrie Smith of Fayette, Hardwick’s successor, heeded this call for construction and began to work in earnest to raise support and funds for the construction of an impressive building that would be not just a base of operations for the League but a tribute to the foundational importance of municipalities in the state. In September of 1968, Watkins purchased Lots 37 and 38 in the New Philadelphia Subdivision of Montgomery County, on the corner of Adams Avenue and Bainbridge Street, in shouting distance from the Alabama capitol building. For $60,000, the League had made the first step toward creating a facility equal to the demands of an increasingly urbanized state.

The South Hull Street headquarters, home to the League for more than two decades, could not house sufficient staff to provide the level of member service and support of which the League could be capable. Unlike the modest, low-slung brick building the League currently leased, the new design by Montgomery architecture firm Tom Kirkland and Associates would speak to the aesthetic sensibilities of the time, embracing a more streamlined modernity and bringing added light, air, and space to the staff. Members of the League’s many committees were present as ground was broken on November 20, 1969, and the staff of the League moved into their new quarters 21 months later, only one week shy of the expiration of the organization’s long-standing lease for 24 South Hull Street.

The seven full-time employees found the building clean and spacious, as well as equipped with cutting-edge technology: the League could boast two phone lines and a large workroom with an offset printing press, a liquid copier machine, an electronic stapler – in short, everything needed to print the monthly newsletter in-house. Twice a month, the entire staff would roll up their collective sleeves and lock themselves into the workroom for marathon sessions to hand-collate and staple the publication, stuff copies into more than 2500 envelopes, sort the envelopes by zip code, band the sorted envelopes and pack them into mailbags, and finally load up the League’s station wagon with all the heavy mailbags, with staff member Clarence Lee then driving the overburdened vehicle to the post office. Despite everyone’s best efforts, the publication production line didn’t always run like a well-oiled machine – on several occasions, staff reporting for work in the morning would get their days off to slippery starts, as the copier had spent the previous evening leaking, creating ink slicks that covered the floor and made office traffic rather treacherous.

Laying the Foundation for Growth

While overseeing the construction and opening of the League’s new headquarters, Watkins was also shepherding important legislation for the growth of municipalities through the Alabama House and Senate: in 1967, cities and towns were constitutionally enabled to increase their debt limits substantially; two years later, municipalities were allowed to adopt true sales taxes; in 1971, municipalities were invested with the authority to annex property to their municipal limits (when given unanimous consent by property owners). Put together, these measures meant that Alabama’s towns and cities could more easily fund expansions of their services and increase their square mileage to keep pace with their climbing populations. These League legislative victories become even more impressive in the context of the radically altering political terrain of Alabama that began in the mid-1960s with the election of several Republican congressmen in what had been – for decades – a solidly one-party state. Instead of focusing on lobbying for particular issues and causes, League representatives now had to navigate political parties, too. With its forthrightly non-partisan agenda, the League disdained making financial contributions to political campaigns (a policy still in effect today), and therefore its legislative success had to stem from effectively and persuasively communicating with lawmakers.

If the startling 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy – once a speaker for the Alabama League of Municipalities’ annual convention – abruptly ended Americans’ romance with the White House, the scandal bubbling around President Richard M. Nixon in the early 1970s soon completely eliminated any starry-eyed notions about the intrinsic nobility or accountability of office-holders. When five men were arrested inside the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters in the posh, curvilinear Watergate office building in Washington, D.C. in 1972, the nation began slowly to realize that involvement in the break-in and its attempted cover-up extended all the way up the administrative and executive food chain in the nation’s capital. By the time President Nixon resigned under threat of impeachment or worse in 1974, the ramifications of his above-the-law actions had cascaded down to the state and local levels of governance. On the last night of the Alabama Legislature’s 1973 regular session, lawmakers created the State Ethics Commission and passed a new law requiring exhaustive financial disclosures from elected officials, appointed officials and board members, and their families. As a result of this new law, many municipal officials and legislators didn’t seek reelection, as they found its demands invasive and unreasonable. The League worked ardently to highlight the problems inherent in the too-sweeping law, even filing a lawsuit to protect municipal officials and boards. In the face of the resulting Circuit Court of Montgomery’s ruling, the Legislature retooled the law in 1975 to enact more-reasonable parameters of disclosure.

With the introduction of the Municipal Workers Compensation Fund in 1976, Watkins and his team found another way to fortify Alabama’s towns and cities. The League-sponsored insurance pool offered municipalities of all sizes affordable alternatives to the steeply increasing rates – and sometimes denied coverage – of private insurance carriers. The Texas Municipal League introduced this concept, and the Alabama League became the second in the nation to provide peace of mind (at a manageable cost) to its constituent municipalities. Executive Director Watkins would serve as the Fund’s General Manager for its critical first decade.

Passing the Torch

As the 1970s came to a close, the League continued to crusade for municipalities’ financial security and self-determining capabilities. When the Alabama Supreme Court opened the door for unlimited damages to be sought in lawsuits waged against towns and cities, the League effectively closed and deadbolted it, crafting legislation passed in 1977 that capped liability in the low hundreds of thousands of dollars, protecting municipalities and their taxpaying citizens from potentially bankrupting awards. Thanks to the League’s efforts, in 1980, municipal governing bodies were finally empowered to determine their officials’ salaries rather than having to entrust the state legislature with the task, ensuring that qualified candidates for municipal office could better afford to pursue public service. In the early 1980s, Alabama’s voters ratified a constitutional amendment that socked away revenues and royalties from offshore oil and natural-gas drilling into an irrevocable trust fund, the interest of which was to be controlled by the state legislature. Working cooperatively with the Association of County Commissions of Alabama, the League successfully secured a piece of the trust-fund pie for Alabama’s towns and cities: when the total interest on the fund exceeded $60 million in any given year, municipalities could access 10 percent of that interest for use on capitol improvements.

On that victorious note, Watkins retired from the League of Municipalities in May 1986 after thirty years of service. During his tenure as Executive Director, he had written what became standard primers and reference books for Alabama’s municipal officials, The Handbook for Mayors and Councilmembers and Selected Readings for Municipal Officials, and he served two terms on the Board of Directors of the National League of Cities. He passed the reins of the League to Perry Roquemore, Jr., whom he had hand-selected from the 1973 University of Alabama School of Law graduating class to be the League’s new Staff Attorney. During the twelve years they worked together, Watkins became an influential mentor for Roquemore, both professionally and personally. Watkins’ quiet competence and graciousness made him a popular figure with the League and municipal officials long after his formal retirement – in fact, for the seventeen years until his death in July 2003, he maintained active involvement with the organization and its members.